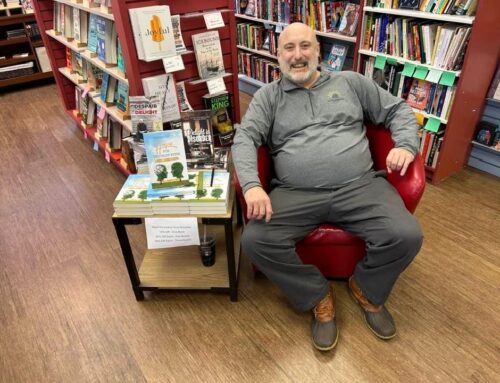

Diane Rabinowitz retired in 2018 from a lifelong career as a teacher. She grew up in New York, but except for a short stint in North Carolina and ten years in Kentucky, has lived the majority of her life in California. She has wide-ranging interests in health, the arts, and fitness, but her main focus since moving from Los Angeles to a small town in Northern California is to make her community more hospitable for the homeless and those with serious mental illness. She has been developing friendships and working relationships with anyone who is similarly devoted so we can create better care for the most vulnerable. Her life-long devotion to Buddhist practice sustains her.

Dear Tariq,

I want to tell you how much I love you, and how happy I am that you are finally in a care situation where you have recovered much of your self. In some ways you are doing better than you ever have, even before you got sick. You are reading now, you are communicating so well now about your activities, your thoughts, your feelings. You are not afraid of your feelings, you are caring for yourself in ways that I’ve never seen before. It is truly a miracle and a wonder of prayers answered, sufferings endured.

I remember when I got that first call from the police telling me that you were in trouble and I needed to get home now. They had you in a squad car. They asked me if I had seen the wounds on your arms and legs. I had only seen one of the wounds the previous day; I had asked you about it and you said it was nothing, you just fell skateboarding. It turned out that you had large burns on your arms and your legs, and we had to take you to a burn specialist for him to make sure they did not get infected. Days later you insisted on going to your friend Raymond’s house, after his mother told you you were not welcome there. I chased after you and had to call the police. I did not and could not understand your behavior but I felt it was dangerous. I had no way to deal with the trauma we were both experiencing other than to ask for help from those who were supposed to defend and protect us—the police. They showed up with a large fire engine, an emergency vehicle, and a couple of police cars. You were sitting on the curb. One of the fire men engaged you in conversation and I heard you tell him you burned yourself. When they finally got you in the ambulance, they took your blood pressure. It was off the chart. You were so anxious. I was so scared.

They took you to the hospital, and you were there for a month. Your dad and I drove the 35 miles and sat in traffic both ways that doubled the travel time. Each visit was more suffering. You were very fragile.

Meanwhile, I was learning about a level of suffering that I had never known before. I developed much deeper compassion and empathy for my students, so I was able to do my job better. But I still was afraid because I didn’t know how to help you. We tried family therapy. We tried having you see a psychiatrist. We tried putting you in a day program, but they hospitalized you. You weren’t getting better. Finally, I realized that my insurance company was not going to help me get the treatment you needed, so I turned to the county, where we had our first successful engagement with treatment.

I was so proud of you when after a year of working with your case manager, your therapist and psychiatrist, you were able to go to college. I was thrilled that even though math had become harder for you than it had been before, you worked hard, you joined a study group, you had a girlfriend, and you seemed happy. You were taking piano lessons and you were actually learning to read music and play with two hands! Practice was paying off! You were starting to be able to play pieces well. But it was during that third semester that things started to go bad. I saw you during the Christmas break withdrawing and not feeling so well, and you wouldn’t talk to me. I knew you were going out with friends and I had a feeling you were starting to smoke pot again. But I didn’t realize that even though you had registered for a couple of classes, you weren’t going to those classes. Instead you started hanging out with some people that were scary to me.

I became very alarmed. It was evident that you were no longer taking your medication. Since the agency “graduated you” from the Full Service Partnership, you were not getting the support you needed to work through your challenges. I became filled with dread. We started fighting because you were lying to me, and I felt you were putting me in danger with the people you were hanging out with. Each time I called for help from the PET team, you were able to behave in a way that they didn’t believe you needed to be hospitalized again. But I knew there was something seriously wrong and I was frustrated that no one would listen to me.

Finally you told me you wanted to leave home and would I write you a check from your college money. When you left with your belongings in a duffle bag, I felt dreadful. And when my house was robbed, I had a feeling it was you and your new friends.

For the next 8 years it was homelessness, jail, failed treatment over and over again. I was actually relieved when you were in jail, because at least I knew where you were, I could visit you, and you weren’t homeless. Yes, there were dangers to being in jail. But after the third or fourth time, they had started a mental health wing at the jail and you actually had a clinician to meet with and they were giving you medication. I’m sure it wasn’t ideal. But Dr. Weiss became a good friend to both of us, and believe me, he has helped us get this far. You have been conserved for 3 years now, and we have finally been able to get you into a treatment facility that has worked wonders. I pray every day that the support you’ve gotten will continue so that you may continue to recover yourself and have a safe, healthy, fulfilling life. My faith and my joy have deepened tremendously over these 12 years of suffering and struggle. I pray that you will find a faith that you can turn to, that sustains you. I am grateful for you, my son, my greatest gift in life.

From the Editor: If you have a brain illness or care for someone who does, please consider submitting a love letter for this Hope for Troubled Minds project. Letters should be no more than 1,000 words and should be written directly to your loved one (anonymously or by name). Send your submissions to tony@delightindisorder.org with “Love Letter” as the subject.