In Elie Wiesel’s Night, Eliezer is a Jewish teenager, a devoted student of the Talmud from Sighet, in Hungarian Transylvania. In the spring of 1944, the Nazis occupy Hungary. A series of increasingly repressive measures are passed, and the Jews of Eliezer’s town are forced into small ghettos within Sighet. Before long, they are rounded up and shipped out to the death camps of Burkenau, and Auschwitz. Throughout this slim narrative, Eliezer reflects on the nature of God in response to the atrocities he witnesses. In one pivotal scene, he describes the execution of three Jews, among whom is a young child.

One day, as we returned from work, we saw three gallows, three black ravens, erected on the Appelplatz. Roll call. The SS surrounding us, machine guns aimed at us: the usual ritual. Three prisoners in chains – and, among them, the little pipel, the sad-eyed angel.

The SS seemed more preoccupied, more worried, than usual. To hang a child in front of thousands of onlookers was not a small matter. The head of the camp read the verdict. All eyes were on the child. He was pale, almost calm, but he was biting his lips as he stood in the shadow of the gallows.

This time, the Lagerkapo refused to act as executioner. Three SS took his place.

The three condemned prisoners together stepped onto the chairs. In unison, the nooses were placed around their necks.

“Long live liberty!” shouted the two men.

But the boy was silent.

“Where is merciful God, where is He?” someone behind me was asking.

At the signal, the three chairs were tipped over.

Total silence in the camp. On the horizon, the sun was setting.

“Caps off!” screamed the Lageralteste. His voice quivered. As for the rest of us, we were weeping.

“Cover your heads!”

Then came the march past the victims. The two men were no longer alive. Their tongues were hanging out, swollen and bluish. But the third rope was still moving: the child, too light, was still breathing…

And so he remained for more than half an hour, lingering between life and death, writhing before our eyes. And we were forced to look at him at close range. He was still alive when I passed him. His tongue was still red, his eyes not yet extinguished.

Behind me, I heard the same man asking:

“For God’s sake, where is God?”

And from within me, I heard a voice answer:

“Where is He? This is where – hanging here from this gallows…”

When I first read this, in the context of a liberal theology class, we discussed how this was evidence of the “death of God.” The God that had perceived and perpetuated by the Biblically literal Christians died at the death camps. Now, the task of contemporary theology is constructing a new way of being, a new understanding of “what it means to be a human”.

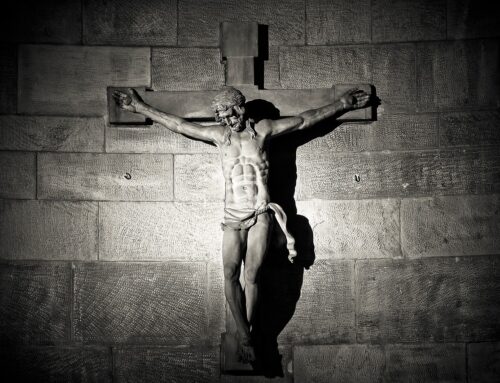

I don’t know what Wiesel intended this passage to mean (and to a large extent, it doesn’t matter – the task of interpreting literature does not rest primarily with the author). What I find most compelling is how closely it parallels the death of Christ. Three executions. One child (often presumed “innocent”). A Jewish child killed by agents of the government. The agony of the hanging child “lingering between life and death” echoes the One who cries out on the cross “My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?”

In a sense liberal theologians who interpret Wiesel’s passage as evidence of the death of God are right. God did die in Christ on the cross. The “little pipel” is a Christ figure and when he is executed, the Spirit of Christ dies in a very real sense.

But this is not the whole story. Even Wiesel doesn’t end the story there. Night is only the first of a trilogy and, while Wiesel’s characters wrestle in their relationship to God, God is very much alive.

For those who have ears to hear, there is much good news. Where is God? God is preparing a home for us in Paradise, seated on the throne of grace, and moving within and among us today, leading us through the darkness of death into the joy of abundant life.

Considering what is happening in the world at the moment, it can’t be too much longer – please God – before Christ returns and ends all evil. The story of ‘little pipel’ reminded me of the movie, The Boy in the Striped Pajamas. Heartbreaking. I don’t care what all the liberal theologians say, I know where God is… He’s with me. He’s standing right next to me holding my hand just like He was three weeks ago when I was diagnosed with B-Cell Lymphoma. I have complete and total peace.

You are so right, Lynn. I praise God for your peace. I will pray for Christ’s healing such that you can best give glory to God in your life. Please stay in touch, as you are able. You mean a lot to me and many others.